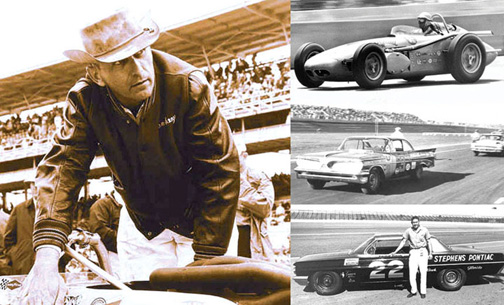

Smokey Yunick

Where are the Giants today?

I don’t think it is just me asking that question. And, I hope it isn’t just age (you know, the older kind) that has me pondering such things. I am serious when I ask. All we see today are race drivers being treated like rock stars or Hollyweird actors. The adventure is missing. Everything is orchestrated by publicists and managers. They show up at races with their entourage and support crews. Mingling with fans is a well-planned photo op. Where are the real Giant figures that made automotive racing the exciting, ga-zillion dollar business it is today? Where are the Smokey Yunicks?!

These icons of the racing days-gone-by are like the old football quarterbacks who would run a ball no matter how hopeless it seemed, because.... well, because they had it, and it was their job to do. How many times do you think Bart Star laid down on the nice soft grass to avoid being tackled? Men like Smokey Yunick were of the same ilk. They took their jobs seriously and put their entire being into it. And, at the end of the day, they were just like everyone else.... not a celebrity, but a man with to job to do.

Some of us are old enough to have met men like Smokey and enjoyed their special views of life and work. Some of us even remember seeing him and his crews and cars doing their magic during what most of us consider the most exciting, formative years of auto racing. And, like all Pontiac lovers, we hold dear those years in the late-50s and early ‘60s when Smokey Yunick campaigned so successfully those cars we love the most.

But, Pontiac is only a small portion of this amazing man’s long auto racing and engineering career. He is gone now, but we continue to celebrate all his accomplishments and his charisma which helped make this such an exciting part of Americana. Young engineers and racers of today... you have some mighty big shoes to fill. Might I suggest that in addition to all your computers and publicists, you study some of the greats like Smokey Yunick and take a few chances, push a few limits, and do a little piloting by the seat of your pants now and then. If you fail, so be it. But, if you succeed, the rewards will be even sweeter.

The following is to Smokey... a true Giant!

The following is what was said about Smokey Yunick by the MotorSports Hall of Fame, where he was inducted in 1990.

A sly mechanical genius whose reputation as one of the premier mechanics in NASCAR hasn’t diminished over the years, Henry Smokey Yunick was the “Best Damn Race Car Mechanic” who worked out of the “Best Damn Garage In Town,” in Daytona Beach, Florida.

His expertise helped shape the careers of several drivers, among them champion Herb Thomas, who won the Winston Cup title in 1951 and again in 1953 and the great “Fireball Roberts.”

Yunick was born on May 25, 1923, “somewhere around” Maryville, Tenn. When he was 16, he tried his hand at motorcycle racing. The affair was short-lived but he did earn his nickname from it by piloting a cycle that had a habit of pouring out engine smoke. A fellow competitor who had trouble remembering Yunick’s given name of Henry simply called him “Smokey.”

Yunick became a member of the Army Air Corps during World War II and once, while in the air, he admired the view of Daytona Beach and decided to live there. He moved to the city in 1946.

He opened his garage in 1947, the same year he began working on race cars. He worked with Marshall Teague, who assigned Yunick the responsibility of preparing a Hudson Hornet for Thomas for the second Southern 500 at Darlington (S.C.) Raceway. Thomas won the race and went on to enjoy several successful seasons with Yunick, who soon became the car owner.

Yunick raced Chevrolets for a couple of seasons (1955-56) and then hooked up with veteran Paul Goldsmith and Ford in 1957-58. Together, they switched to Pontiac and stayed with the car through 1962, taking on Roberts and Marvin Panch as drivers, among others. Yunick’s cars won four of the first eight major stock car races at Daytona International Speedway, starting in 1959. Roberts won three of them. In 1963, Roberts won the pole in a Yunick Pontiac, but lost the race to teammate Panch when the engine blew with 13 laps to go.

Afterward, Yunick continued to field stock cars from 1963-68, with the likes of such greats as Banjo Matthews, Bobby Isaac, Darel Dieringer and others driving for him. From 1958 through 1975, Yunick made 10 trips to the Indianapolis 500, with Jerry Karl his driver in his last effort.

Yunick’s ability as a mechanic not only produced winning cars and drivers, it helped bring innovation to technology. Stories about his “sleight of hand” in car preparation abound, but he maintains their telling over the years has embellished them significantly.

The fact remains, however, the man from “The Best Damn Garage In Town” knew racing. And he gave to it far more than he took.

Read on, and learn even more about the exciting career of Smokey Yunick in the following article from Hot Rod Magazine.

The History of... Smokey Yunick The Unique

Remembering Racing’s Legendary Iconoclast

By C.J. Baker and Gray Baskerville

Henry Yunick started life 76 years ago as a “po’ country boy,” as rod patron George Poteet described his own humble Mississippi beginnings. Yunick remembered that in his early Pennsylvanian childhood, after his father died, he had no time for books– although it was the subsequent information he gleaned from physical science books coupled with his own natural mechanical bent that made Smokey the wily legend he became. At the age of 12 he built his own tractor scrounged from parts he found in a junked car, and he started racing motorcycles at age 15. That ol’ bike smoked so much– set up as loose as possible because Yunick had an intrinsic feel for clearances and internal dynamics– that it caused a track-side announcer to call him Smokey. He should have named him Lucky.

One of Smokey’s major contributions to circle track racing was his deep appreciation for and use of aerodynamics. Smokey’s familiarity with how air affected objects in motion didn’t just happen. Yunick spent the better part of WWII flying heavy bombers over both friendly and unfriendly territory. He survived more than 50 missions in the Balkan theater including 20-plus round-trippers to Ploiesti to blast the Germans’ oil-refining capabilities in Romania. He also did training and checkout missions over peaceful territory– including a mission over friendly Florida checking out Daytona Beach. Yunick’s new post-war digs weren’t exactly random. Historically, Daytona has been the speed racer’s hauly grail since 1902 when Ransom E. Olds and Alexander Winton staged a racing duel on Ormond Beach in the northern section. This confrontation between two pioneer car-builders heralded the beginning of Daytona’s 32-year involvement with land speed racing. Among those sand-stormers were Stanley-Steaming Fred Marriott (127 mph in 1906), Blitzen Benzing Barney Oldfield (131 mph in 1910), Doozie Tommy Milton (156 in 1920), and Frank Lockhart, a 1926 Indy winner who died the next year in a spectacular crash while driving his supercharged, Miller-powered Blackhawk Special. A native of Glendale, California, he tested his car at Muroc before taking it to Daytona. His example led to our involvement with the dry lakes that continues to this very day.

By the early ’30s, Daytona’s ever-shifting sands and course-altering tides caused the Americans and Brits to shift their LSR (Land Speed Record) attempts to the Bonneville Salt Flats, but that didn’t end Daytona’s beach-racing. In 1936, the city fathers promoted a vacuum-filling stock car race by developing a circle track south of town comprised of both the beach and a parallel access road. Two years later (1938), Bill France and Charlie Reese took over the beach/road races and ran them until the war broke out.

With the end of hostilities, France resumed promoting Daytona’s unique beach-road race in 1946. One year later, two events occurred that would forever change the face of circle track racing. First, Smokey came to Daytona to open a truck repair shop because, he said, it looked so good from the air. Meanwhile, Bill France saw that stock car racing– for all of its good-ol’-boy, booze-running roots– was fast becoming a popular spectator sport. France determined that, with a little organization, promoting southern-style stockers could prove to be a lucrative undertaking. So he took the initiative and founded the National Association of Stock Car Automobile Racing: NASCAR. The guy who survived all those air missions over Eastern Europe and the Pacific was quickly caught up in this other form of survival soon after he opened his Best Damn Garage In Town and began a second life that still defies description. You might say that Smokey’s career began the instant after a kindred soul by the name of Marshall Teague walked into his garage. Teague, a well-known stock car driver and car owner, happened to be a Daytona Beach resident, too. He took Smokey’s slogan seriously and invited him to join his team even though Yunick told him he knew nothing about stock car racing. However, the eclectic garage owner knew where to gain an insight. He began studying the chemistry and physics books that he had collected during the war to find out how Mother Nature worked. The information he gleaned from his collection helped him discover the easiest way to make a car go through the air or how long a racing engine would run before it, in his words, “blowed.”

But the book that Yunick studied most was the one containing NASCAR’s new rules. In a piece entitled “Inside Smokey’s Bag of Tricks,” C.J. Baker quoted Smoke thusly: “You have to understand that when I got into this thing back in ’47, they didn’t have near as many rules as they do now. You could run whatever you thought you could get away under what NASCAR would call ‘being within the spirit of competition.’” This happened during what Smokey would later call his drinking days. Baker remembers Smokey telling him that people would come by the race shop for a few drinks, and the next thing he knew his competition was sniveling to France. “If you did something they (NASCAR) didn’t like, which was pretty much up to Bill France, they would fine you or throw you out of the race as ‘being outside the spirit of competition,’ even though there was no specific rule against the supposed infraction.”

Teague’s cars of choice were the new step-down Hudson Hornets– based on inverted-bathtub styling powered by an inline flathead six. The Hornet’s low center of gravity and dual carburetion and other special 7-X “export” items made it fast for its era. And with Smokey at the wrench, the combo rendered Teague hard to beat. Yunick was either a crafty, devious, underhanded, rule-bending, no-good, cheating SOB (one view), or a master of ability, hard work, careful preparation, common sense, and the scientific approach (the other). Smokey’s M.O. was simple: If the rulebook didn’t specifically outlaw this or that, then it was OK to do this or that. No porting or polishing was allowed, so he would paint the ports with hard lacquer and sand them to a mirror finish. Or he would pump an abrasive slurry through the intake manifold runners to remove the lumps and bumps. NASCAR said no boring or stroking, but there was no rule against offset cranks. There was a rule against using lightweight flywheels, but there wasn’t a rule that prohibited removing the ring gear, laterally drilling lightening holes in the flywheel, then reinstalling the ring gear. “All those other guys were cheatin’ ten times worse than us,” remembered Yunick, “so it was just self-defense.”

During the early to mid ’50s, Hot Rod ’s editorial package took on a wider scope. Our traditional lakes, dirt track, and salt-flats racing was now being augmented by professional circle track coverage. By 1955, Wally Parks, Tom Medley, Ray Brock, Bob D’Olivo, and Eric Rickman began to attend, photograph, and cover circle track’s two major events: the Indy 500 and Daytona Speed Week. And with then came Smokey.

Yunick’s parallel lives began in 1955 when Teague and Chevrolet’s Ed Cole– the father of the small-block Chevy V-8– pulled him in two different directions. First, Cole hired him to beef up Chevy’s factory racing program. During his three years under Cole, he helped develop the Black Widow, sorted out its Rochester fuel injection, and hired Paul Goldsmith (a champion motorcycle racer) to drive both his stock cars and his first Indy roadster. A couple of months after Cole signed him up for Chevy duty, Teague invited “El Smoko” to hang with him while he drove a car at Indy. Indy’s thin rulebook and white paper car construction enchanted him. He “hung out” for three years before making his first move. In the meantime, Smokey quit Chevrolet after the ’57 Daytona race when his deal with Ed Cole soured, and he quickly entered a brief but warm affair with Ford and team captain Pete DePaolo. Ford got out of stock car racing in 1958, and Smokey’s close relationship with his mentor Bunkie Knudsen and John DeLorean quickly led to a Pontiac program with pole-winning results (1959 to 1962).

For the record, qualifying 40-plus years ago at Daytona was totally unlike what is done today. In keeping with its land-speed heritage, every car had to make a timed, Bonneville-style, top-speed run down Daytona’s famous beach. The fastest got the pole. During a top-speed test session prior to the running of the Daytona Beach race in 1957, Smokey discovered air was building up under the hood, causing the pressure-sensitive Rochester injector to go dead rich. There are two versions of how Smokey cured this problem. Either Goldsmith opened the heater door during the race to vent off the air, or Smoke installed a couple of pressure-relieving ducts in the Bel Air’s toe board. Whatever. Goldy was able to pick up 20 mph and may have won the race if he hadn’t burned a piston with only six laps to go.

Smokey’s switch to Pontiacs didn’t sit too well for the NASCAR establishment after he won the pole at the new Daytona speedway in 1959, 1961, and 1962. Yunick– never one to go along to get along– P.O.’d the Ford and Chrysler factory teams with his pole-sitting privateers. The factories sniveled to France, who was afraid of losing their support, so he had his inspectors give Smokey’s cars the ultimate thrice over. This nitpicking eventually led to Smokey’s lifelong feuds with both the Senior and Junior France.

Although motorsports history has treated Yunick and stock car racing as fraternal twins, he considered the Indy 500 to be his greatest challenge. After a three-year learning curve (1955 to 1957), he had stepped up in 1958 with his own car driven by Goldsmith, who he considered to be his greatest driver. Although they made the 33-car field, Goldy was involved in a multi-car crash and out of the race with 199 laps to go. Yunick returned in 1959 with what he called Smokey’s Reverse Torque Special, driven to a Seventh-Place finish by Indy great Duane Carter. In 1960, Yunick hit a home run. He and Chicky Hiroshima teamed up with driver (and team manager) Jim Rathmann to win it all in the Ken-Paul Special. Of interest is that Rathmann needed more pit help so he hired Bruce Crower and his team after Crower’s Chevy-powered roadster failed to qualify. Smokey would field two more Rathmann-owned and -managed cars and one of his own before he stood the Brickyard on its collective ear. How? With “The Wing”.

The third consecutive year. Rathmann’s first qualifying attempt on the second day of qualifying, Sunday May 13, was too slow, and the crew waved him off. On Wed. the 16th, Rathmann took to the track with an inverted wing mounted to his car. Crew member Bruce Crower prepared a wing in an effort to increase downforce and speed. This was the first wing ever seen at the Speedway, and one of the first on any racing car. They were subjected to the jibes of other drivers and crew about the “sunshade.” In practice, the wing enabled Rathmann to be clocked in the corners at 146 mph, at the time the fastest cornering speed ever at the Brickyard. But the increased drag prevented the car from going much faster than 146 on the straights. There was no time to fabricate another wing with less drag. Rathmann qualified in 23rd spot at 146.610 mph on the third day of qualifying, Saturday May 19, without the wing. In the 1962 Indy 500 , Rathmann moved up steadily through the field to be in 10th place at the 150-mile mark. He held onto the group of cars behind the lead pack and advanced as high as 7th in the order, but was unable to challenge the leaders and finished 9th in the ’62 500. Rodger Ward won by at a record speed of 140.292 mph. The following year, the USAC prohibited wings, and despite aerodynamic experiments in other forms of racing, the ban at the Speedway would not be lifted until 1972.

In 1964, Yunick showed up at the track with one of the most radical cars ever to enter the 500-mile race. Called the Hurst Floor Shift Special, it featured a catamaran-like layout with the driver placed in a pod adjacent to a second pod containing the engine, front and rear suspension, fuel tank, and radiator. Unfortunately, his driver Bobby Johns– the guy who almost won the Daytona 500 with Smokey’s Pontiac in 1960– had trouble adjusting to the car’s handling characteristics and eventually backed it into the wall during the last day of qualifying.

Yunick took a couple of years off from Indy to go gold prospecting in Ecuador. However, he continued his NASCAR involvement, having made the switch from Pontiac to Chevrolet in 1963 when Knudsen moved to head up that division of GM. Smokey was immediately invited to take a look at the new engine that their engineers were working on– a 427ci big-block designed to replace the obsolete 409. A number of the porcupine-head “mystery motors” were produced and raced at the ’63 Daytona 500, though Chevrolet pulled out of stock car racing a month later in March of 1963. Yunick continued as an independent on the sly, building, racing, and winning with a series of imaginative Chevelles, including his Curtis Turner-driven ’66 pole-sitter. This game lasted as long as Knudsen was at Chevrolet, but when he switched to Ford in 1969 after a losing bid for the GM chairmanship, Yunick went with the boss.

After a two-year hiatus, Yunick returned to the ’67 Indy 500. The boys at Goodyear made him an offer he eventually couldn’t refuse. Goodyear would give him money to buy the car and hire Formula 1 champ Dennis Hulme to drive it; and he drove it to a Fourth Place finish. Goodyear borrowed the car and a spare engine after the race but never returned them.

Smokey’s ongoing troubles with NASCAR over his getting competitive reached its zenith in 1968. Yunick blamed both Ford and Chrysler for putting so much pressure on France that he had his tech inspectors overscrutinize his super-slippery Chevelles. Legend has it that when Smokey’s ’68 Chevelle picked up its sixteenth violation, he got in the car and drove it back to his garage in Daytona with the fuel tank still sitting in the inspection area. His parting shot was, “make it 17.” Two years later, Smokey said adios to NASCAR and was out of stock car racing.

After Knudsen joined Ford, he asked Smokey to begin developing a stock-block pushrod engine for the Indy 500. There was no time to sort out the new powerplants, so he obtained a Gurney Eagle and armed it with a DOHC turbo Ford (of course) and had Joe Leonard drive it. While running Second to eventual winner Mario Andretti, Leonard had a stray hose clamp puncture his radiator. It took Smokey and his crew 13 minutes to install a replacement. Still, he finished a respectable Seventh. Knudsen left Ford in 1969, and Smokey switched to a series of 207ci, turbocharged Chevrolet stock blocks which he ran until 1975 when United States Auto Club’s Dick King declared pushrod engines had no future at Indy.

For the next 10 years, Hot Rod and Smokey enjoyed a close working relationship thanks to C.J. Baker and Buick’s Herb Fishel, who loved Winston Cup racing and also had an interest in high-performance street rodding. During the late ’70s, he saw a chance to make the Buick V-6 the ’80s alternative engine to the Mouse motor and hired Smokey to further refine the engine. Baker and Yunick then combined forces to produce a series of articles entitled “Turn of the Century” which chronicled the development of the Buick V-6 using as many heavy-duty OEM parts as possible. The result was a 355-horse V-6 streeter that found itself in a ’78 Roadmaster, which was ultimately taken to Riverside International Raceway and test driven by NASCAR-champ Cale Yarborough.

In 1979, Baker and Yunick teamed up for two other projects. One was a supercharged V-6 that was installed in a Deuce highboy roadster built for former HRM editor Lee Kelley by Total Performance and driven by Baker and you-know-who from Memphis to California. The other project was a 355ci “what-if” alky-burning, Hilborn-injected small-block. The boys at Indy were contemplating a return to normally aspirated engines, and Smokey couldn’t resist building a prototype V-8 using parts form his enormous pile of former racing inventory. The engine produced an easy 675 horses, but USAC’s return to a normally aspirated stock-block formula never materialized. Smokey wrote it off as another “green card” fiasco and went back to working on his controversial hot air engine.

Smokey Yunick would spend the rest of his life (1985 to 2001) immersed in projects that ranged from exploring numerous alternative energy sources (wind, geothermal, wave action, solar panels– everything but nuclear because waste disposal troubled him) to writing a “Dear Smokey” tech advice column for Circle Track magazine. When he developed leukemia last year, he did the Smokey things– first by becoming a body dyno for experimental cancer treatments while at the same time finishing his three-part autobiography, reviewed by Jeff Koch below.

During my one-week stay at Daytona in 1984 to cover the 500, I spent Thursday afternoon with Smokey on the beach taking photos of his hot-air-engine–powered Fiero. He couldn’t believe that I would deliberately miss the two, 125-mile Winston Cup qualifiers to be with him. That still amazes me. One hour with Smokey was worth a day watching taxicabs crash. In fact, if it hadn’t been for the guy wearing whites, a greasy hat, a pair of horn-rim glasses and smoking a pipe– and who, by the way, ran the Best Damn Garage In Town– there wouldn’t be a Daytona 500, let alone a NASCAR.

It was a 7/8 scale Chevelle created by Smokey that led NASCAR to create the infamous patterns they use on all cars today. Here is an excerpt from an article by Karen Van Allen on SpeedFX.com about that car:

“‘Cheating,’ as it were, has been around since the inception of stock car racing. The year 1966 produced two of the most notorious violationsof rules quite possibly witnessed in the sport of NASCAR racing - and believeit, or not, both cars passed technical inspection prior to the Dixie

500 at Atlanta. Junior Johnson’s “Yellow Banana” Ford Galaxy and Henry “Smokey” Yunick’s

”little” #13 1967 Chevy Chevelle, complete with an offset chassis, raised floor, roof spoiler,

balloon in gas tank and a host of other brilliant rules book interpretations. NASCAR finally disqualified Yunick’s creation in 1968 when it was found to be some 200 pounds underweight.”

Smokey Yunick was a real thorn in NASCAR’s side. He was more inventive and just plain good about cheating or “bending” the rules than anyone ever was or will be.

Who was Smokey Yunick?

Highlights: Grew up on a farm in Neshaminy, Pennsylvania • Flew B-17s for the Army Air Force in WWII • Flew for the Flying Tigers • Driver, mechanic, crew chief for stock cars in 1950s and 1960s • Won two Grand National (Winston Cup today) Championships• Won Indy in 1960 • Worked in Ecuador in oil drilling and gold mining • Wrote for Popular Science and Circle Track magazines

Accreditations: Founding Member and Director of Embry-Riddle University • Honorary Doctorate in Aeronautical Engineering, Embry-Riddle Engineering • Professor Emeritus, Daytona Beach Community College • S.C.O.R.E Judge, for three years, one of ten judges picked to examine annual alternate energy expo submissions from American colleges and universities, related to alternate energy • Member of Society of Automotive Engineers

Patents & Inventions: Variable Ratio Power Steering • Hot Vapor Engine • Silent Tire • Smoketron Engine Testing Device • Movable Race Track Crash Barrier • Oil filling through oil filter • Extended Tip Spark Plug • Power brakes from residual power steering pressure • Water bypass system for “V” engines • Reverse cooling system • Centrifuge Type Oil Refinery (Ecuador)

Awards: Two Time NASCAR Mechanic of the Year • Mechanical Achievements Awards– Indianapolis Motor Speedway & Ontario Motor Speedway • Engineering Award– Indianapolis Motor Speedway • Inventor of the Year– 1983 • Presents the Annual Smokey Yunick Lifetime Achievement Award at Charlotte Motor Speedway

Hall of Fame Inductions: National Racing Hall of Fame • International MotorSports Hall of Fame • Legends of Auto Racing Hall of Fame • Stock Car Racing, Daytona Hall of Fame • Darlington Motor Speedway Hall of Fame • Legends of Performance– Chevrolet Hall of Fame • TRW Mechanic Hall of Fame • Living Legends of Auto Racing– 1997 • Stock Car Racing Magazine Hall of Fame • Michigan Motorsports Hall of Fame • Voted #7 on list of Top 10 athletes of the Century by Winston Salem Journal, Oct. 1999 • University of Central Florida, President’s Medallion Society • Rotary Club of Oceanside– Daytona Beach

Race Record: 1951-1954– 39 Grand National Wins after 1954 • won Raleigh- August 20, 1955 • won Darlington- 1955 • won Palm Beach- December 11, 1955 • won Wilson, N.C.- March 18, 1956 • won Langhorne- September 23, 1956 • won Greensboro- April 28, 1957 • won Lancaster S.C.- June 1, 1957 • won Raleigh- July 4, 1957 • won Daytona Beach- February, 1958 • won Atlanta- July 4, 1959 • won Daytona Beach- February 12, 1960 • won Atlanta- July 31, 1960 • won Daytona Beach- February 24, 1961 • won Daytona Beach- February 26, 1961 • won Daytona Beach- February 10, 1962 • won Daytona Beach - February 16, 1962 • won Daytona Beach - February 18, 1962 • won Daytona Beach - February 22, 1963 • 57 Stock Car/Grand National races • Won Indy race- 1960

www.pontiacregistry.com

Thanks to Pontiac Registry.